I met Vladimir at M.I.T. in 1990 and we were married in 1995. I called him “Vova” but most of our American friends called him “Vlad.” He was a private person, very cautious about sharing information from his past. But in the summer of 2006 he asked me to write down some of his memories and thoughts. We worked on this project in our free time until 2013. He would talk–stream of consciousness–and I would type as fast as I could. The blog posts filed under “Life Stories” are from those sessions.

Life Stories

Vladimir: Memories

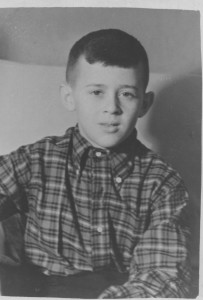

“My earliest memories are from kindergarten, from some kind of medical check-up. I remember standing in line naked, with girls, and feeling very, very embarrassed. Memories are strange; some details I remember perfectly, others are just like hints of things, like just a scent that you go around, sniff and get a little hint of it…”

My father Mois Barsukov

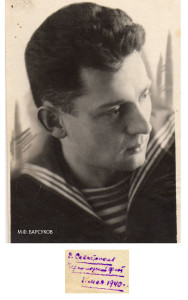

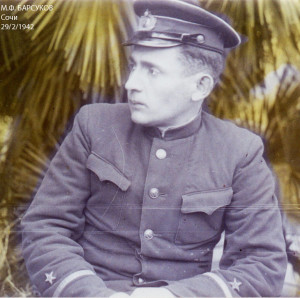

As far as I know, my father Mois Barsukov was in the military for nine years; he was a submariner and an officer in the marines. Shortly after my parents were married in 1939, my father was sent to fight in the war between Finland and the USSR. There was no break for him between this war and what Russians call The Great Patriotic War or The Great War for the Homeland—the USSR’s war with Germany.

In 1944 my father was wounded with a concussion and was sent to Tbilisi, Georgia, and my mother joined him there; it must have been their first opportunity to spend much time together. After my father was well enough to work he was assigned to teach in a military school called Nahimovskoye Uchilische. He taught astronomy among other things. He was teaching at this school when I was born, just a few months after the Great Patriotic war was over. I was born in January 1945 in a private house on Krilov Street in Tbilisi.

This school where my father worked was a military academy for orphaned boys. There were five or six such campuses in different cities. The goal of these schools was to take boys from the streets and turn them into well-educated and physically trained officers. The boys even learned ballroom dancing. Some of these schools are still in existence, but the one in Tbilisi where my father taught closed in 1955. Unfortunately the archives of the school are lost, but some enthusiastic former students have started a website. They are collecting pictures and documents and trying to build up a history of the school.

I ran across their website one day and sent an email to the webmaster. I was surprised to get a warm reply from a real person: Valentine Maximov, nicknamed “Fregat” (frigate). I’ve had several long email exchanges with him, and he has shown strong interest in learning about my father. He asked for photos and dates, and then finally he asked me what my father was called. This caused me to pause.

My father’s full name was Mois Itshok Fiselevitch Barsukov. Barsukov is not a Jewish name; it’s a Russian name, and how my father’s family came to have that name is a puzzle to me, because we are Jewish. The rest of my father’s name–Mois Itshok Fiselevitch–is clearly and obviously Jewish. Also, my father often went by two different first names: Mishe or Sashe. Not Mois. And what is more, some people called him by the middle name Fyodorovitch instead of Fiselevitch. These other names (Mishe, Sashe, and Fyodorovitch) do not sound Jewish—they would be more typical for a Russian than a Jew. So when Fregat asked my father’s name I was uncertain how to answer. I worried that if I told him my father’s real name he would not want to deal with me because of the anti-Semitism that is still so common in Russia. And besides that, I don’t actually know what my father called himself at that time.

My father’s full name was Mois Itshok Fiselevitch Barsukov. Barsukov is not a Jewish name; it’s a Russian name, and how my father’s family came to have that name is a puzzle to me, because we are Jewish. The rest of my father’s name–Mois Itshok Fiselevitch–is clearly and obviously Jewish. Also, my father often went by two different first names: Mishe or Sashe. Not Mois. And what is more, some people called him by the middle name Fyodorovitch instead of Fiselevitch. These other names (Mishe, Sashe, and Fyodorovitch) do not sound Jewish—they would be more typical for a Russian than a Jew. So when Fregat asked my father’s name I was uncertain how to answer. I worried that if I told him my father’s real name he would not want to deal with me because of the anti-Semitism that is still so common in Russia. And besides that, I don’t actually know what my father called himself at that time.

So in the end I only gave the last name and unfortunately my father’s name has not been found yet among the documents about that school.

My father was always attracted to and attractive to women. He married more than once, but for as long as I knew him, he always carried a picture of my mother in his wallet and her picture hung on the wall of his apartment.

Sara Gitlin–my mother, and Maria Gitlin–my aunt

My father told me that I had a baby carriage from America. America supplied a lot of things at that time—so maybe that was not so unusual. But the story is that the baby carriage was given to my mother by a General in the military school where my father was employed, whose intentions were questionable. My mother Sara was an attractive woman, I was told. She looks beautiful in the few pictures I have of her. But I never knew her, because she died when I was nine months old.

The Great Patriotic War was over for Russia in May 1945, and my mother died a few months later at the age of 36. I was told that she had typhoid and that someone gave her a piece of bread, which was like poison for her system. I have no idea if this is true, but this is what I was told. I was told a lot of things but I never had an honest conversation with my father about my mother, even though my father lived to be 84 years old and immigrated to the U.S. with me. I was always afraid to hear the truth from him, and I am still piecing together many mysteries of my own life and his.

For example, I remember hearing that I was sent to St. Petersburg from Tbilisi when I was a baby. It probably means that my father took me there hoping one of his brothers or sisters would help with me, but that did not happen. Instead, I was sent hundreds of miles away to Samara (at that time called Kuybyshev, USSR), where I was raised by my mother’s sister—my aunt, Maria Markovna Gitlin.

My aunt Maria Gitlin (“Manya”) was a kind and wonderful person. I called her “mother” and for a very long time I was not told the truth, though I suspected something was not right because I overheard whispers of the adults. My father, who lived in St. Petersburg, often sent parcels and sometimes he visited us. Since I knew he was my father, naturally I assumed that he was my aunt’s husband. Instead of being told the truth, I was under the painful impression that my father had left my mother and that he lived with another woman in St. Petersburg.

Another experience made me question my identity. My aunt often locked me in the room when she had to go out. She probably did it for my safety but it was frightening to be locked in a room alone. I still remember the shape of the keyhole and trying to make a key from a piece of bread or a piece of paper to get out. When I became old enough to read, during these times I found letters my aunt had written, searching for her lost husband. This was her tragedy; her husband had disappeared during Stalin’s time. But I only understood her pain later; at the time the tragedy for me was the dawning realization she was not actually my mother.

Where are you from?

When I meet someone new they almost always ask me this unwelcome question: “Where are you from?” I usually reply “I’m from Cambridge” hoping this response will stop their questions. I’d rather not talk about my past with strangers, but it’s always obvious to people that my accent is foreign, not regional, and they want to pin it down. To me, my accent is like a fingerprint to a criminal: impossible to get rid of. Maybe there is even more than the accent–something intangible that indicates I am from a different culture. Sometimes I wonder what it means to know a language and whether it is possible to really learn a language when you start at age 44.

Language and culture are so strongly entwined that you can’t separate them. When I lived in the Soviet Union the word “kupitz” (to buy) was replaced in the vernacular by the word “dostatz” (to get). Why? Because you couldn’t just go to a store and buy what you wanted—most of the stores were empty. So to “get” something you either had to stand in a long line or know someone who had been fortunate enough to get it by standing in the right line. It got so that if you saw a bunch of people standing in line, often you would just get in that line and ask people “sto dayut?” (what are they giving?), because it might be something you wanted. There is a joke related to this. A guy gets in a long line, asks “sto dayut?” and is told they are selling cheese, which he wants. Finally he gets to the front of the line, gets his piece of cheese and begins to eat it. But it tastes terrible because it is not cheese but soap. (The soap and the cheese in the USSR looked alike.) Nevertheless he continues to eat it, saying “ya tibya kupil, ya tibya s’iem” (I bought you, so I will eat you).

To obtain books was even more complicated. So many books were banned by the government. And if not banned they were published in such small quantities that they were precious, almost like currency. (Except books about communist leaders, which no one wanted to read—they were everywhere, like dirt.) If we heard that an interesting new book might possibly come out, people would go and stand in line at a bookstore just on the chance that the book might come in to the store.

A foreigner would not understand the phrase “sto dayut?” or the cheese vs. soap joke, or the difficulty getting books, without an understanding of Soviet reality. So in the same way I suppose people will go on asking me “Where are you from?” But I plan to keep on replying “I’m from Cambridge.”

A Dream

July 22, 2009

Last night I dreamt I was in Russia and there was a huge airplane flying overhead. It dropped something enormous and at first I thought this thing looked very interesting and intriguing, like a giant sculpture. But it turned out to be a huge net and it dropped on me; I was trapped along with some other people. But a guy near me had a cigarette and we were able to burn a hole in the net. Pretty often I dream that I’m in Russia and I get caught, and in these dreams I’m thinking that I’m an American citizen and I can get away.